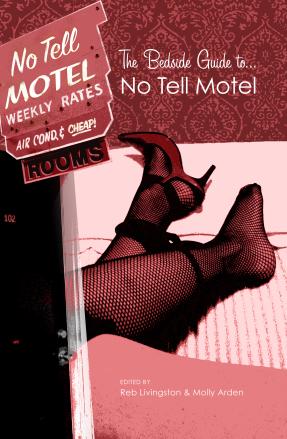

The Bedside Guide to No Tell Motel

Edited by Reb Livingston & Molly Arden

No Tell Press, 2006

ISBN 1-4116-6591-0

$16.99

A LITTLE RUDIMENTARY FOREPLAY

I grew up a few miles away from the Coral Court Motel, a notorious cluster of self-ensconced rooms just outside the St. Louis city limits on the stretch of Route 66 that is now Watson Road, a major thoroughfare in south-central St. Louis County. Built in the Art Deco style, the motel had long since seen it's heyday by the time I discovered it in the mid-1980s, when it began to show major evidence of its decline into dishevelment.

Coral Courts was famous for being one of the last motels in the St. Louis area to offer hourly rental rates, and I spent the majority of my high school days attempting to get a bevy of attractive young ladies, either individually or en masse, to bounce the bed springs there with me. I was never successful with these efforts; in fact, I owe a long overdue apology to Wrenn Terrill for four years of unwelcome offers to cover her in chocolate pudding and lick her clean—an offer which, amazingly, not a single girl ever accepted. It wasn't until my sophomore year of college, after a particularly heavy night of drinking and carousing, that I realized chocolate pudding stains look identical to shit stains, hence the reluctance I continually encountered.

Alas, it was with great regret that I saw Coral Courts torn down in 1995 to make way for a small subdivision of McMansions without ever having stepped inside one of the rooms for a bit of heavy foreplay or a quick fuck. My wife does not like me reminiscing aloud about these missed opportunities, and I had almost forgotten about them.

How nice, then, to have discovered this treasure trove of discreet trysts that bring all those lovely high school lusts back to mind.

OKAY, ENOUGH WARMING UP

Culled partly from the archives of the online lit journal No Tell Motel, The Bedside Guide to No Tell Motel contains a lusty mix of poems by poets who display not only the love of language, but intimate knowledge of the arts of seduction. While the editors have certainly constrained themselves to a narrow theme, what better theme than sex?

Edited by two self-proclaimed "housewives" of the non-desperate variety—Reb Livingston and Molly Arden—this book tingles with eroticism both charged and subdued. Although the editors go a bit overboard with the sexual innuendo in their introduction, where they claim they've selected poems which "pricked our minds, twitched our senses, and reminded us why we started reading poetry in the first place," they have collected a diverse body of works around a theme that could easily have slid into the pornographic based merely on arrangement.

Flipping through the pages, I was stunned at how many names seemed familiar, and not necessarily because I've read them at No Tell Motel. Lance Phillips, Catherine Daly, Betsy Wheeler, Aaron Anstett, Jilly Dybka, Aaron Tieger, Steve Mueske, Jenni Russell, and Shanna Compton are but a few poets whose work is featured herein. These are poets who are all over the blogosphere, poets whose online poetic efforts have garnered the attention of fellow writers. Publishers Weekly, despite being late (as usual) to spot a trend and despite ignoring (as usual) the vast number of women writers who blog, has it right: poets have created a vast and thriving online presence. But that presence is one that still has to resort to do-it-yourself publishing to get their words out.

While Jessa Crispin (founder of Bookslut.com might hate self-published books because they seem to have the taint of the desperate and disheveled, Livingston and Arden have produced a gorgeously readable book utilizing Lulu.com, a print-on-demand publisher. While many mainstream and small press publishers are turning to POD for purely economic reasons—it allows them to keep backstock to reduced levels but still keep a large number of titles "in print"—using POD to distribute an anthology of work based on their critically successful web journal is a savvy move to showcase their journal and move viewers/readers to their web site, where they can indulge in the "poet of the week" format which has become the journal's trademark.

The book is structured in four sections—Discretion and Its Discontent, Parsing Body Language, Techniques Guaranteed to Please, and The Difference Between Seduction and Manipulation—each of which is a better title than the book's. Ostensibly, the sections should move the reader from seduction to consummation as the book unfolds. But these divisions are just a gimmick, which is a shame; often there is no relationship between the poem and the section's theme—or if there is, it is tenuous, at best. The poems could have (and should have) been better organized to mimic the ebb and flow of sexual relationships. But often, poems which appear in the later sections would have been better placed earlier, and vice versa. Richard was right in his earlier post about the Poetry of Men's Lives: An International Anthology: the politics at play in selecting and organizing anthologies are tough to figure out for the reader, but Richard neglected to say that it is imperative for editors to get it right so the reader understands why pieces fall where they do. When assembling an anthology, editors have to make it clear how and why pieces appear as they do, especially when they eschew an alphabetical presentation system. And that is one of the primary problems with The Bedside Guide. It's hard to see how these poems segue into and out of each other. Yes, anthologies are not necessarily designed to be read straight through, but the presentation of work needs to be unified and coherent. Still, The Bedside Guide finds rooms for a vast array of poetic styles and fetishes.

DISCRETION AND ITS DISCONTENT

This is perhaps the weakest section in the book, as it tries to set up and deliver not just the section's themes, but the book's as well. The pieces seem all over the map, leaping from the desire of a young woman at a poetry reading in Laurel Snyder's "To the Man beside Me at the Reading" (which is an excellent poem to open the book with) to Charles Jensen's explanation of the underground world of homosexual prostitution in "Rough Trade" just two pages later. But the standout pieces are found in the middle of this section, Aaron Belz's triptych "My Factotum":

My Factotum

My factotum brings me tea.

Then he stands on his heels, looking

out the bay window.

Hands in pockets, a kind of

George Wallace posture.

"What if none of this is real?"

He muses, a little quietly.

My factotum borrows my keys

to go to the grocery store.

He brings home Rolaids

and a case of AB.

"What if none of this is meaningful?"

He asks, as if no time had passed.

He pours himself a cup of tea.

My factotum tries to figure out

His new digital camera.

He wants to capture the image

of a hummingbird floating

outside the bay window.

My factotum is deaf.

He wants more than he can have.

My Factotum

My factotum reneged on his promise

to take baby munchkin to the zoo

while I was fixing the Datsun.

Instead, he painted pink diamonds

on my corduroys, a project he

was supposed to have finished a week ago.

My Factotum

My factotum lives in France.

My factotum has no pants.

The relationship here seems easy enough in the opening (factotum literally means "Jack of all trades", but is also shorthand slang for a gay lover willing to do anything in the sack (ala the Jack McFarland character on Will & Grace. But the relationship here is souring, first with the inattention and carrying on in the first poem, the broken promises in the second poem, and the free-wheeling pantless Paris sightseer of the final poem. When I read the last of this series, I keep thinking of David Sedaris bemoaning his relationship with his longtime companion, Hugh; I've been reading too many of his New Yorker dispatches. And the hummingbird line in the first poem reminds me of Wilco's "Hummingbird" from A Ghost is Born,a song which echoes these poems's tension in the dreaming for the unattainable, the discontent that drives decisions, the way quiet desperation rises and then abruptly shifts scenes in a relationship. Okay, maybe that's a stretch. But Belz masterfully moves us through a simmering relationship, from the beginning of the the end to the end, the discontent writ large.

PARSING BODY LANGUAGE

This second section tries to focus on the first moves of seduction and how bodies interact (and intertwine). This section features some of the most challenging pieces in the anthology, especially Lance Phillips's (of Here Comes Everybody fame) "I act as if the bodies that are acting upon itself were acting upon it and were causing its perceptions." A sprawling multiple perspective poem, at first it reads like flarf, a seemingly disconnected sprawl of word association and stream of consciousness vomit on the page that abandons narrative. But upon a third read, I suddenly saw that behind its challenging typographic leaps and Burroughsesque cut-ups was an inner-voice / outer-voice engaged in a fantasy/reality dialogue that does an intricate dance which ultimately leads to the act of mutual (self?) gratification. It's an interesting take, one that is as disembodied as this section gets.

This section also features a poem which should win a best title award, Carly Sachs's "In Response to Pussy," which dances around the vulgar names for female genitalia:

In Response to Pussy

A least give it a name for Christsake's.

How about Jane? Jane is a nice name,

not too flashy, not one that you'd give

to your daughter anymore, so pretty much

safe, the only exception being the Dick and

Jane reader, but kids don't use that anymore,

and it's difficult to make metaphor out of

simple sentences. Pussy has more potential

for that. I mean, referring to a woman's genitalia

as feline: a playful housepet. Which also happens

to end in y, masquerading it as cutesy, like

when girls change their names to end

in that y sound so they sound more perky,

like Angie, Rosie, Kathy, Carrie so their names

roll off the tongue like candy. But oh, the irony,

pussy isn't sweet or sugar-coated. Albeit, it's

not as bad as cunt, kooch, or yoni, but it's slang

for weak, timid, unmanly.

And vagina is problematic. It sounds so mechanical.

I didn't even know it until Mrs. Kessler went around

the room shaking all the girls' hands saying "hello vagina,

how are you? Nice weather we're having isn't it vagina?"

I went home thinking that it was just another word for girl

so I announced proudly that I was no longer a girl,

but a vagina. It was such a big impressive word,

but mom screamed and said not to call it that,

but call it Virginia and to never let a man go there.

So I said what about West Virginia and mom said only dirty

men want to go there. So then I asked her where Ohio was

and she laughed and said not to worry about it since I wasn't

Jane and didn't live in Virginia.

Even though this piece has a great title, the problem with this poem is that the first stanza is too obvious, too trite in a post-Vagina Monologues age. We all know the associations between vaginas and Dick and Jane, cats, etcetera, and so the poem has to rely on tone alone—a tone which starts out scornful and sarcastic and then pretty much just bleeds away into nothing. It isn't until the second stanza that the poem really kicks into gear; the first stanza is a throw away, just idle chit-chat to bring us to the true confrontation between the speaker and her mother—and this stanza is a completely different tone than the first. Here, we've moved into the confessional, but it doesn't keep for long until we get a pat ending which wraps things up too quickly. I wanted to see more about Mrs. Kessler's off-putting introductions, the Mother's sage advice to the daughter. Here, the subject matter goes from being proud to being shameful—which I found totally unsatisfying. I wanted to see this poem wrap back around to the proudness, as the conferring of names is an act of ownership, of acceptance, and this poem waffles it by playing the hand too quickly. It reads like a workshop poem, a poem that is trying too hard to impress the reader and not hard enough at getting to what needs to be said. There's too much setup, too much spinning of wheels until the poem begins to take off before it crashes and burns in trite cuteness that it accuses its subject of.

The "poem written in response to a word" poem is a tried and true workshop exercise—but often the results read like Sachs's. This poem represents perhaps what is wrong with The Bedside Guide—too many poems read like drafts, not finished work. Yes, they are catchy, funny, and sometimes catch us off guard with their honesty, but a poem that isn't finished is still a poem that isn't finished. For a contrast on how the exercise succeeds, see Marta Ferguson's "In Defense of Orgasm: For a Friend Who Has Aesthetic Problems With the Word," also in this section, which starts off with an in-your-face question and consistently develops its rhetorical stance:

In Defense of Orgasm: For a Friend Who Has Aesthetic Problems With the Word

So tell me, what would you

rather say than orgasm?

You want something like kohl?

Élan? Panacea? Or maybe triptych?

Something cleaner? Quieter? Tell me,

please, you wouldn't shorten it for kicks.

I mean, orgasm has all the sounds.

What other syllable could you use

at the outset? How else do you

convey the original moan? The sound

that swells in your throat until

your lips open in orisons of praise?

Then, of course, there's the rest

to be considered. The throaty growl

that follows the moan, the rich

thrum of swollen arteries, the rough

entanglement of tongues, the friction,

the rub of hair and reddened skin.

The, ah, gasps. Sharp. Indrawn.

That follow the growl, that open up

the oh, arrest the vibration, the hum,

the pulse. The starpoints of light in

the blood-dark moments when we are

both alone above our actual bodies.

And the downcycled mmmm...

the body's lower idle, the human purr,

the velvet luxury of release, relent,

repetition. The warm homemade buzz

of busy endorphins scattered like elves

at work in the sweetness of our separate selves.

Your problem, honey, is articulation.

Do it right, and the deed speaks for itself.

The obvious contrast between Sachs's and Ferguson's poems is immediately clear: the former deals with the word's associations, the later with the word itself. But beyond this treatment of subject matter, Ferguson's poem is clearer in tone, cleaner in form and structure, and knows its purpose from the outset. It is a true defense of the word which, in its explication of phonetic associations, does not make wild, unannounced leaps in focus. This is a poem which gets it right.

Another poem in this section which gels as a whole is Kim Roberts's "In Virginia," a poem which, tempting as it is to borrow Sachs's vagina/Virginia association, has nothing to do with sex, but everything to do with desire:

In Virginia

The light rises from the boxwood

and hovers just above, like an extra skin.

Those heavy clouds furrowed

around our hilltop all week

have broken up, split apart,

and the sun is glinting off the wet earth

like drum beats delineating

bush, truck, pond.

Even the pathway

to the barn shines, humble asphalt

beatified. But especially the boxwood.

I never liked it so before.

A skin of light, surfaces pocked

with baroque patterns and lifting.

I wish I could feel my skin

lifting, infused with visible desire.

Here, we have another tight poem which maintains its consistent tone (in this case, awe). Roberts's tone is unified, and her metaphors controlled: the idea of "an extra skin" surfaces in each stanza in different guise. The metaphor itself is an extra skin that doesn't need to be shed, but embraced. The desire here is a desire for oneness not with a human lover, but with the all and everything, a grand unification. But it's all based on a simple observation, a clarity of sight that comes in a master stroke. Roberts focuses her poem on light and perspective, but it is the changing of desire that is key here. The shift of the eyes to a new position reveals new possibilities, and in doing so creates a renewed interest in the mundane—for what could be more mundane than a common shrub?

What sets both Ferguson's and Roberts's poems apart from Sachs's is their use of poetic language beyond prose. Whereas Sachs's poem reads like prose broken into lines, both the other two use poetic devices to heighten the language beyond the casual and conversational. This demands greater attention on the part of the poet; the poem is what needs to be said, not what the writer wants to say.

TECHNIQUES GUARANTEED TO PLEASE

This third section finds the editors finally getting it right; all the poems in this section are a delight to read, and the sequence makes both logical and thematic sense; we move from inhaling the scent at the nape of a neck in the first poem to reading hilariously mistranslated erotica in the last, and are delighted along the way. Perhaps the best place to start, though, is Cami Park's "Sugah":

Sugah

Sugah says, baby, come fix my hair

Sugah says, baby, come zip my dress

Sugah says, baby, come rub this sweet lotion all up and down my legs

Sugah says, oh

Sugah says, baby

Sugah says, come

Sugah sugah sugah my sweet baby sugah oh

What is not to love about this poem? The anaphoric use of "Sugah says, baby" at the start of each line echoes the child's game "Simon says" and moves us, willingly, into the seduction. There is something about the simplicity of this poem, the way the speaker draws in the unnamed lover with simple imperatives, that speaks of wanton desire unlike any other poem in the section. The speaker clearly intends to seduce, to move the lover to do her bidding, and we know where it will lead, and we want to see it unfold. When I read this, I hear Gwendolyn Brooks's voice in my head—I can't help it. It's not that this is particularly written in Black English, as pronouncing "sugar" as "sugah" is more a Southern dialectical mannerism than it is an indication of race. But the straightforwardness here, the savvy manipulation (which perhaps should place it in section four instead of section three) are something one would expect in the best of Brooks's short pieces. Parks gets it right, and this must be a fun piece at readings; even my text-to-speech synthesizer pauses, inflects, and intones at all the right places.

A poem totally unlike "Sugah Says" in tone, but still about desire is Steve Mueske's "On Desire," a poem which appears to respond to James' Wright's "A Blessing". Taking his cue from Wright's famous final lines "Suddenly I realize / That if I stepped out of my body I would burst / Into blossom", Mueske ponders how desire takes root and enthralls:

On Desire

If I could burst into bloom, red

with the rose of it, with the rise and swell

of it, called into being through

the deep green, and trembling with light,

I might understand. If I knew

how light touches water

with a tracery of trees, gifts

the world as it is not, I might know

why I am not a rose or water or light

but a man who suddenly believes

in witchcraft. What else

but this hollowing fire, this mark

of the thaumaturge, could make

the wild heart, so like a bird, thrash

in its cage? Imagine rain and wind,

portrait of tempest with shed: shivering

slivers of wood, the whole structure

in danger of imploding. Here under

a black sky swirling with clouds

I am ready to be unmade. The air

is charged and blue, and my hands

are burning with light.

Again, here is a masterful poem, where desire takes gothic shape: tracery, witchcraft, thaumaturge, tempest: desire as black magic. Yes, it is a metaphor older than Shakespeare—but in Mueske's hands it takes on a renewed cloak, as desire is both a love and a jealousy which strikes the "wild heart" and makes it throb beyond control. Mueske captures emotion but leaves it unresolved, the air aflame with ions and the speaker trembling, on the verge of bursting into blossom. It's allusions aside, this poem stands as one of the best in the section. We'll be reviewing Mueske's recent book in an upcoming post on TGAP; I'm looking forward to seeing what our reviewer has to say.

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN SEDUCTION AND MANIPULATION

In this closing section, the editors drift away from narrative forms, which is perhaps the only thing unifying the poem. Take for example, the two poems which are paired next to each other, Emily Lloyd's "Plummy" and Noah Eli Gordon's "An Acoustic Experience":

Plummy

She stuck in her thumb and pulled out a plum. I didn't know it was in there. I don't know what she did with it. How it felt to have it, hold it, know where it had been.

She stuck in her thumb and pulled out a plum. I helped her a little this time. I was wet and pushed while she pulled with that thumb of hers. Enjoy the plum—baby?

She stuck in her thumb and pulled out a plum. By now I was worried, worried. My wife! I said. Is probably! [tug] Saving! [tug] That for breakfast!

She sticks in, pulls out. Plums just keep on growing, there in the dark. She'll stop by, flash a light on me, pull one out, and retire for the evening.

Sweet? cold?

I have not once felt her hands.

An Acoustic Experience

Inoculate with ones & zeros

the sound of the human voice

You have a computer's unrequited compassion

& I, the outline of an ostrich

torn in half, tacked to a pixilated heart

The perfect companion's a photograph of sand

Unexpanding, elegant universe

something something something the end

In "Plummy" we get straight narrative in prose form (I hesitate to call it a prose poem, as I'm not seeing exactly what is poetic about it, but then I'm dense). The lover pulling plums out–of where we're not told, but it's easy enough to guess——and unlike Jack Horner, doesn't seem necessarily proud of this achievement. In fact, it seems tiresome after a bit...for the speaker as well as the plum-puller. And just what is the guy doing with all those plums? Does he eat them, or what? And notice how pretty soon, she doesn't even need him anymore—she can pull those plums all on her own. As read as code words to sexual gratification this piece speaks for itself. It's narrative all right, but as coded and loaded as we'd expect post-modern narrative to be.

But Gordon's piece, on the other hand—what to make of it? It is perfectly aural, and that's it. It doesn't need to make narrative or literal sense, it exists only for the love of the sound, and when you take those words and feed them through a text-to-speech generator ("inoculate" the words into binary code) the words sound just as delightful. Manipulation of words is the manipulation of sense, and who needs others when one is seeking self-gratification by playing with words? Why not have a picture of sand to keep you company? Who needs the human voice when the likeness of humanity can be summoned at the click of the mouse? Some say he's just another flarfist, but I've been a fan of Noah Eli Gordon for a number of years because as he works on an aural level and creates rhetorical devices based on invented grammars, he is quietly reconfiguring lyric poetry.

BETTER THAN A COLD SHOWER

All in all, while I'm attracted to many of the poems in the anthology, I'm a bit underwhelmed by The Bedside Guide as a whole. There are a number of pieces that would have made the collection stronger had they been excluded (such as Sachs's). And there are some pieces that would have been better played off each other had they been arranged closer together; Bruce Covey's "Fountain" would have been the perfect poem to follow Snyder's opening "To the Man beside Me at the Reading," for example, but it is instead buried seventy-three pages away. Nonetheless, the majority of the poems here are worth reading, some if only for a momentary thrill. After all, even bad sex is better than no sex at all.

Ultimately, Livingston and Arden have given us a book which explores the sensuality of seduction in all its intricate forms. True to their introductory words, the poems they have selected are sometimes coy, sometimes serious, and often tongue-in-orifice. The editors return to the slush pile this summer to work on a follow up. I'm pulling for a parody of the Gideon Bible.