Bob Stanley even had some dittos that he had kept from that class and dittos of one of Sternberg’s poems that he had written for a workshop. That poem “The Ant” was in Sternberg’s most recent book Bamboo Church (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003).

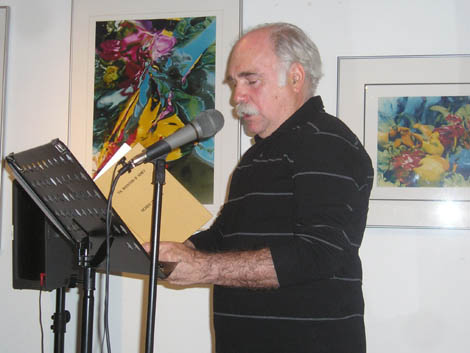

Sternberg led off the evening and read a series of poems from his earlier books The Invention of Honey and The Map of Dreams. He started with “Meal,” “The Prince Soliloquy,” “In the Metro,” and a poem addressed to an unkind reviewer. He followed with “The True Story of My Life,” and “The Pelican in the Wilderness,” He also read some sections from his long book-length poem sequence “Map of Dreams” before he read selections from Bamboo Church, such as “Two Wings,” “First Dance,” “Plateia Kyriakou,” and “Supply=Demand.”

After a lengthy intervening open mic session (during which yours truly contributed to the tedium), Stephen Yenser opened the evening with selections from the book of poems devoted to Dorothea Tanning’s surreal paintings of imaginary flowers. The first piece he read was derived from 3 lines of a James Merrill poem, and the piece was given the title of the Latin genus and species name appended to Tanning’s fictitious flower, namely “Merrillium trovatum.” Yenser then went on to read a piece from the same collection that he had written for one of Tanning’s fictitious flowers (which coincidentally opens his new collection Blue Guide.) The poem was entitled “Love Knot.” Yenser proceeded to read several other poems from Blue Guide. He read “Paradise Cove,” “Helen’s Zen,” “MRI: A Trance,” “Variations on Ovid” and selections from Skafian Variations.”