Who remembers the ditto machine? On Saturday, I listened to San Francisco’s Susan Terris read her wonderful poems about the ditto and other bygone machines. Machines that were the envy of their time. Then on Sunday, I read an interview with Robert Hass, in which he talked about the mimeograph, and about how changes in technology have changed our ability to access poetry.

He said, “The difference I'm aware of is that young poets and would-be poets, through the Internet, have immediate access to a whole range of possibilities they didn't before. When I was a kid in San Francisco, I could find my way to City Lights Bookstore and mimeograph poetry magazines. If you were growing up in Worcester, Mass., you were out of luck.”

Hearing Ms. Terris and reading Mr. Hass over the weekend prompted me to reread a recent Subtletea.com interview with Cantara Christopher on Monday. The interview is timely and provocative and may be of interest to readers of the Great American Pinup. Her small press provides an example of the changing landscape of publishing and how technology is “increasing our range of possibilities.”

Here’s a quick sketch. Ms. Christopher co-founded Cantarabooks and the literary magazine Cantaraville with Michael Matheny. When they found themselves at loggerheads with the mainstream publishing world, they decided to strike out on their own. The result is an innovative blend of the new and the old publishing paradigms. Ebooks, paperbacks, and a literary magazine that is only available as a pdf file. Here’s how she described their venture to David Herrle in the Sutbletea interview.

“From the outset we decided not to operate like the more established small presses. Recent innovations in technology had created a New Paradigm, a new book world where it was possible for anyone at all to be published by Lulu.com for less than ten dollars; where an enterprising author could self-publish her novel, aggressively market it and make the New York Times bestseller list, like M.J. Rose with Lip Service; where a farsighted publishing company could make its fortune selling instantly downloadable ebooks of erotic fiction to women in the Midwest, like Ellora’s Cave. If anyone can write and publish a book, why publish under someone else’s imprint?”

Ms. Christopher answers her own question.

“The missing element has been editorial presence: the opportunity to collaborate with disinterested professionals possessing the skills to help shape and clarify a work; to gain prestige by being published by professionals with high standards of excellence. To participate in the eons-old Literary Dialogue, in other words. Until about twenty years ago, before the age of bottom-line gatekeepers, an author could submit directly to St. Martin’s or other independent press in the certainty that someone there would at least seriously read and consider his work. When the foreign conglomerates started buying up our country’s largest publishing houses and mandating them to concentrate foremost on profits, we were robbed of the aesthetic guidance those houses had traditionally provided.”

If you’d like to read more, follow the link to the complete interview.

http://www.subtletea.com/cantarachristopherinterview.htm

And follow the link below to read my 2006 review of Stephen Gyllenhaal’s Claptrap: Notes from Hollywood, from Cantarabooks.

http://greatamericanpinup.blogspot.com/2006/09/claptrap-notes-from-hollywood-by.html

As for the “tiny fists” in the title of this posting, it refers to Cantarabooks’ motto: “Beating Our Tiny Fists on the Big Hairy Chests of the Corporate Literary World.” Check them out at www.cantarabooks.com.

Wednesday, April 23, 2008

KEN BABSTOCK—AIRSTREAM LAND YACHT

Remember in poetry when you used to be able to get credit for a mind that moved in interesting ways? Now it’s just incessant talk of markets, markets, markets . . . how do you get a reader to swallow so that it can move like crap through a golden goose? Or you might measure who’s got the biggest one with demographic studies that seek to prove how Americans have moved beyond the word and are now looking at the pictures. Perhaps the loss of this form of valor is due to the fact that in the U.S. we no longer make anything and this fact can make us hope we can market our way out of our own mess.

However, in Canada, there seems to still be a focus on that which is more interestingly wrought, for which the gold standard is not what is most immediately accessible to a larger market. At least that is the case with Ken Babstock’s Airstream Land Yacht. Finally, after so many poetry books on the American market designed to capture the attention of this group or that group, we have a book, a major prize finalist at that, which forsakes the saleable niche and aims for the big questions again. The star of Babcock’s book is consciousness, and Babcock pushes his star to the point of breaking, and to the point of many other adjectives: crystalline, shivering, blackness, coated (in oil), off-and-on monitor, blackly stumped, Imperial. For Babstock it is almost as though the will to cerebrate is the will to live itself.

In the title piece, which appears towards the end of the book after many dense ruminations and hyperdriven narratives, Babcock equates an antique Airstream trailer to that of his consciousness. His consciousness is his Airstream Land Yacht.

Airstream Land Yacht

Where in the world to go, to go?

O where in this world to go?

This big old wagon’s slow, it’s slow.

My beautiful wagon’s

slow.

It shines a silver sheen, though,

its silver sheen a-glow,

This silvery ovoid’s sturdy, ho!

metallic armadil-

lo.

Born in nineteen six-and-oh, and Oh,

she’s factory clean.

Awesome to behold but slow, but slow;

she’s sort of like a

brain.

She’s sort of like a model brain, no?

Just sits there unless towed.

And a constant need to unload, to forego,

what we couldn’t take or

know.

The intimation in this piece is that his consciousness is too big and bulky to make a streamlined path through the media debris. It hangs on to places develops wind resistance in all the meaning it tries to extract. This year’s model of consciousness is much more stripped-down. It moves quickly enough to keep with the traffic, and there is very little storage for those who are inclined to stop at garage sales to load up on ephemeral bits. In fact, you can often watch like with the Prius, the progress of its mechanical function take place on the screen.

Or perhaps Babstock is making a comment on the state of consciousness in general which is just not built to keep up with the barrage of information of the everyday, the cutting from one application screen to another screen, the absorption of thirty different commercial contexts in an hour, then still needing room to pack in the news. How many sites have you surfed since you started this paragraph?

Though this is just the sad tale of the medical profession speaking. When I ask my programmer brother, he feels that the human brain is definitely designed for speed.

Yup. This is your brain. This is your brain on Internet hyperlinks. How fast can your brain move from context to context? Do you think it was designed to move that fast? A doctor says no. A software designer says yes.

Babcock seems wired for speed and possesses a good sized hard drive, but I like how he handles recall errors, errors of slippage, such as in his delightfully funny address to Christian (no doubt Christian Bök). Towards the end, of “Think, Pig” (the title itself cribbed from Beckett) he writes:

something he could

in good faith call

a project which might

take me years but

would leave me

in good stead with

certain people

in Buffalo, I said

Christian do you

remember Abraham

and Isaac and that

terribly sharp cleaving

instrument and

the talking shrub?

That “terribly sharp cleaving instrument” is, of course, a knife, and the fact that he “forgets” the name of this weapon, an item that would most likely sharpen the focus of attention on it, makes the poem even more of an immediate gesture. One attends to the speech act quality of the poem. It also reminds the speaker of the brain’s fallibility, both the speaker’s and presumably Bök’s (or God’s as the case may be). Whatever the case, we know from Gödel that any system (in this poem’s case, an algorithm-driven infinite loop of page references) is incomplete. It is incomplete because the system is unable to successfully refer to what is always outside of it. The brain can’t keep up with its context.

This, to me, epitomizes much of Babstock’s work in Airstream Land Yacht. The brain that can’t keep up with its context, but oh how it miraculously tries and it does manage to contextualize a damn sight more than most). It is that kind of effort that keeps me coming back to read individual poems again and again. In his miraculous efforts he covers enough ground with the trace of his consciousness that I want to wind back through the coils of his language to arrive at how Babstock’s compressed language extracts its funky localized meaning at the same time it hammers away on its superstructure.

In one of the “Explanatory Gaps”(there is one for each section: Air, Stream, Land, Yacht) Babstock writes:

Explanatory Gap

Would Form, Colour, and Motion please report to Area 17

where you’ll be met by Memory and Recognition. An unbroken

field of light is uninformative. The cracks,

the jinks, what won’t cohere or blend but bends, fissures,

falls to the field

or becomes figure. A visual percept is degraded light.

We all like to sound important. I was convinced I’d actually loved

by a hot tinny pain spreading downward from the sternum. She

was gone, though,

by the time the evidence appeared, and I’d moll around the train ditch

of an evening, reading German dictionaries and pulling

loosened spikes

from the tie braces, designing industrial versions of croquet.

Home shot:

through the St. Louis Arch to the CN Tower. Oil derricks and

wrecking balls.

I had no friends for a time. Whether

it happened or didn’t it felt as it did and affected the weather. I

was being fleeced, still I paid

for entertainment. It helped feel worse, and worse was where

lovely numb wet its tongue. I sucked it like a strip of dripping lamb—

From the moment where the brain is administrating its sectors to the bulk of the poem where the speaker is opening and closing many doors that lead to a variety of information holding pens, I, as reader, arc through with him and invest myself in his diet of images and anecdote and emotion. It is particularly exciting how this rich blend avoids becomiong twaddle (which is what happens when I often try to enter into this Friederike Mayröcker-like mode). It suggests that everything might get into the poem but it doesn’t. there is still a highly selective attention occurring. It is an attention that is also perfectly at ease with reflecting on itself, not an easy trick to accomplish without the bugaboos raising their heads and intimating a kind of navel-gazing going on.

The title of the piece helps in this regard. Even though it is willing to provide such an abstraction as “a visual percept is degraded light,” the poem has no pretensions about explaining anything. The explanatory gap is the place where this poem happens. It is the place, presumably, where Babstock places his poetic faith in serving as the locus for his work. It nods and nods and nods but never reveals.

Myself, I had an intense desire to order an gyro after reading this poem.

Another thing that I admire about Babstock’s writing in this book is how adeptly it follows the creed of the old Black Mountain School in its edict that content gives rise to form rather than form bringing about content. There is a lot of variation of form in Airstream Land Yacht. From this I can surmise that Babstock waits for his content to congeal in a manner that his consciousness apprehends, again making (his?) consciousness the star of the book. He describes this himself in an interview with CBC Radio’s “Words at Large”:

I start with a few words that make a particular noise, then I go in search of others. As I'm searching for the others, I try to be simultaneously allowing the new ones and those initial ones to inform me of some kind of appropriate patterning device or guiding principle so that they don't simply dissolve into a meaningless verbal porridge like this sentence…

Similar to many poets, Babstock allows his play [“Sometimes making is play, only that” from “Found in a Sock Monkey Kit”] to be his constitutive method, and then he assembles his various “outtakes” into an “appropriate patterning device or guiding principle.” The organizational impulse comes after, and it is guided by his trust that he will be able to find that organizing impulse afterwards. That kind of confidence that he will find a way to organize his tangle of threads (or it will find him) makes the book a pleasure to read as well. there is no style fatigue that one often finds with highly cerebral poets who find a particular method and then grind it out through the course of 60 to 70 pages.

In Airstream Land Yacht we find the architecture of sonnets, variously end-rhymed (or near-end rhymed) poems, a poem that grows and grows its end-rhymed lines [“Subject, with Rhyme, Riding a Swell”], a poem with open six line stanzas that ends with six aphoristic couplets, ["On the Dream of Union Ceasing”], a stanza mimesis where the first stanza looks, sounds and feels like the first with a few variations but produces a a very different meaning [Epochal”], dialog between texts of Kierkegaard and a hog raising manual, and a list poem of brief instructional language [“A Setting To”], as well as others that are too hard to classify.

In all of this variation one might hear Babcock underscoring his objection to Bök’s insistence on a single rigorous form. his method is to be highly unmethodical.

Further in that same interview Babstock describes the tool of poetry as:

Think of a compact case or powder kit for the mind. Small enough to carry around and helps deal with blemishes, imperfections, swellings that mar our pictures of ourselves and the world. Only it's not always about improvements to the reflected image

Poetry as putting on make up, another metaphor, but one that assumes a “fatigued” self in the morning barely able to cobble oneself together before the whole project falls apart by noon.

In this way, Babstock seems to be making a model (the male counterpart to putting on make-up) of himself. In a poem that uses this metaphor for talking about the construction of the self as well as comment on his poetic project, “Scale Model”

Scale Model

Tricked out in phantom gear, I imagined myself

perfected, at least made better to the extent

that I wanted nothing more, and could hurt no one—

which is when the world disappeared. Or

the world’s model displayed under glass with figurines

passing through parks and purchasing things

and boarding trains at dawn then transpiring, shattered

or melted, receding back into the far hills

of the false. The story of Stories Connected, and I

among them, constructed of them, a notch in the wood

of what’s happened, wound down to a farce, just

a face extemporizing the facts and making a meal

of what it had felt like to be. What had it felt like?

I remember a latch on a low gate; a kiosk on a platform

that smelled of diesel and grease; a rowboat blown

into reeds and the oars in the oarlocks; remember

my flesh on the flesh of another but limbs needed

moving and the air needed stitching with words, or

just murmurs, it all demanded doing and seeing,

removing the black box of immediacy to its place

on a shelf near a pot of dahlias gathering dust and

dying. Alone now, in the glow of an Imperial mind,

I curl to the chilled sense of being other; am bench, bolt-

hole, view of the Baltic coast, brother, or crayon set,

want to be implemented, bent to, used inside

the watched life lived—

“Used inside the watched life lived.” That says it all. Babstock very often uses the things he watches and sees through media (as well as his direct experience) as grist for the mill of his own actions. Experience and his media diet are conflated. Where does one begin and the other end? They appear to be continuous, contemporaneous. He has bridged the great divide that plagues the American scene between those mediatized poets, whom Silliman refers to as the post-avant and those experiential poets, whom Silliman refers to as the school of quietude. Babstock’s world is boisterous and smart, but it does not pursue its own end so that it might live one day serve as great intellectual achievement that may live on in the annals of glory at SUNY-Buffalo.

Babcock describes his writings in Airstream Land Yacht as multi-vocal poems which curiously end up sounding even more like himself. Yes, one feels the stitching but in doing so, one is even more assured that a singular consciousnes has weaved them all together and is talking at you.

It is the immediate removed (“to a shelf near a pot of dahlias”) only to be fed back into immediate experience after it has been filtered through the various sieves of books, emotions, stories, dictionaries, films, instruction manuals, travel brochures, conversations, etc. It is experience writ large with all its distractions and imperfections. He establishes the truth of his poetic project this way.

Each section of the book seems to provide poems that might be derived from “Air,” “Stream,””Land,” but in the last “Yacht” section Babstock seems to spend a lot of time on cruises. Or at least he imagines that he is on them. Most of them seem to depart from Schleswig-Holstein and ruminate on or react to the Baltic Sea. The Baltic is the ominous force that is shaping lives.

The Tall Ships Docked in Kiel Harbour

for Don Coles

Norwegian, Russian, Polish, Estonian.

A spectral mist had curtained the port and spread,

silken, dewy, over the crosded park grounds.

Can we say spectral or even mist, wasn’t

it more like a greased, Baltic fog? We can say

the masts appeared broken, occluded at times;

the water that slapped the low stone rampart

could be heard clearly but relied on inference

to be known or to be there, or, looking back, at the very

least, the edges of things went grainy, lost

substance, and shivered; mothers with kids

in their care sampled baked sweets or nudged hand

crafts on display tables then sank away into

enveloping dampness from which cries of

where are you carried through a muffled din—

No, this would have reached us as

Wo bist du and could we really have

isolated a phrase like that, being new to a tongue?—

An area roped off for children held rough-

hewn, log play-structures, the bark left on so they

looked ribbed and reptilian; metal boxes strapped

to lamp poles spat out cigarette packs if you

thumbed in the coins. We might have thumbed

in the coins. The masts, when they split

the slate-coloured veils, leaned and rattled, or

knocked against parts of their rigging, and small

triangular flags hung limp from the upper reaches

where the masts narrowed. Gulls landed—or terns

landed—on the crosspieces where the sails were

furled and tied like camping gear. It might have

rained, as our feet were soaked through, and we wanted

not to be where we were, but felt also an internal

pressure, like a note left for oneself in a home one

has yet to move into, to look, to take in the thick

beams of each building, the docks buried in fog,

the cider smell and steam from steel vats, the layer

of beaded wetness on things and the people who

handled those things: cups, wallets, paper containers

of food, rucksacks, umbrellas, the odd camera or

brass-handled cane. The ships lumbered away, sniffing

each other’s sterns; someone’s future warmed into

high resolution as love’s rags clapped in a weird wind.

The project is as rudimentary as any creative writing teacher could make it. Scene description. But it is so exquisitely visualized and intensely perceived that the scene is possibly more alive than if one visited it. Babstock goes beyond surfaces, but with the subtle inclusion of the speaker in the scene, “the we who might be thumbing the coins” and whose “feet were soaked through” that by the end of the poem the “someone” whose “future warmed” is almost assuredly a member of that group, that couple. The scene transforms the speaker. It is heartbreakingly rendered and mined for its hidden value. It seems to me a great object study in what can be wrung out of what is essentially a still life.

Oh to be so patient so as to let the scene come to oneself the way Babstock has done in this piece.

Then a few pages later we get “Compatibilist” [3:34] with its interest in compatibilism, the idea that free will and determinism are not mutually exclusive entities in the world. Babstock is not afraid of the overtly philosophical, the big idea. It is a marvel how he can do so much else. As readers we should be obliged to take of this kind of weighty territory as well, territory that too frequently poets in the US fear to tread, or if they do, they do so ponderously. I guess they still grow ideas in Canada. Here in the US we just sell rock stardom.

I will be dipping into this book for a long time I feel. Every time I pick up the book and read a few pages I am indebted to its author for his ability to recharge my own instincts to write. He keeps it thrilling, and I encounter Easter eggs on every page. It is hard to encapsulate within one small space such as this the freshness that is contained in this book. Airstream Land Yacht is certainly one of my favorite books of the last several years.

But probably we should give Babstock the last word on his oeuvre in Airstream Land Yacht:

The Lie Concerning the Work

Most were written at home,

some done away,

a few in a bar,

one inside his head.

Many had a tendency to roam,

some felt grey,

a few went too far,

that last refused to be read.

Thursday, April 17, 2008

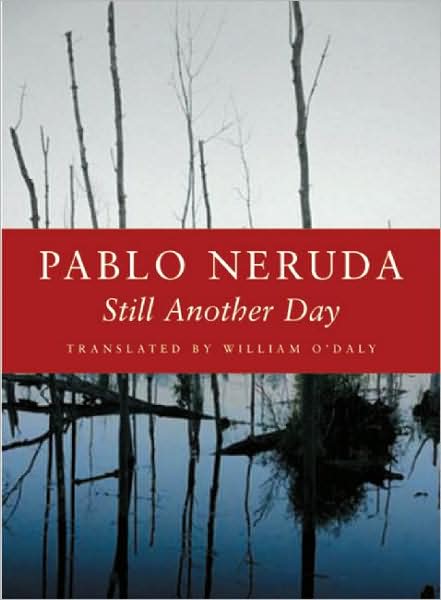

STILL ANOTHER DAY—PABLO NERUDA tr. by William O' Daly

Reading Pablo Neruda’s Still Another Day right after watching Al Gore’s “An Inconvenient Truth” reminds me of how hopeful in his lament for nature Neruda can be, how much his passion for a nation can root itself in a call to remember the spirit. Both of these could be lessons for contemporary Americans to take note of if we weren’t on our own peculiar spiritual trip of consumer satisfaction. Imagine this. A twenty-eight section poem and not one brand name is mentioned.

I have always been fascinated by how Neruda is able to cast his mystical spell over a reader by invoking a spray of disparate objects in his catalogs. Neruda at his best seems to intuitively understand the quality possessed by each object he invokes. He expertly picks each object for its right weight and sound. The disparate nature of the items he invokes establishes the breadth of his eye and mind, and I think this is what is most contagious for me in Neruda’s work. Perhaps this expansiveness might seem alienating to an American reader for whom the poem is a well-heeled display that never wanders from its frame, the way a contemporary American grade school student never wanders off his/her task and drill.

In this rather slim volume of twenty-eight short poems that Neruda wrote just before his death in 1973, William O’ Daly tends a very spare and taut line as one might expect in these poems that serve as guides and meditations. O’ Daly describes this long poem in twenty eight parts in this way:

The reader might experience this long poem as a sequence of distillates or perhaps crystallizations, clarified visions of recurrent themes, charged with the poet’s urgent need to consider them one last time

Like Gore, Neruda is concerned with his country’s land and soil as the essence of the nation, that element to which all humanity and history returns and is reborn. In the introduction O’ Daly describes the influence of the Araucanian indians’ resistance on Neruda and how their resistance, resulting in La Frontera, a borderland wilderness on the edge of civilization, makes itself present in the early poems of this sequence. O’ Daly also comments on how Neruda’s ear for the Mapuche language (of the Araucanian) as a child manifests itself in Neruda’s line, using hard vowel sounds that stand in contrast to the melodic runs.

Mostly Still Another Day is the story of Neruda’s attachment to his homeland. He tells us this in section VI

VI

Pardon me, if when I want

to tell the story of my life

it’s the land I talk about.

This is the land.

It grows in your blood

and you grow.

If it dies in your blood

you die out.

Clearly, Al Gore must have been channeling Neruda. Each one of Neruda’s spree of things named is like Gore with another one of his gleaming graphs of data. The cumulative effect is of a world perilously hanging on the edge, waiting for some breath from the south to breathe life back into it.

Neruda writes short poems that address Yumbel, Angol, Temuco, Clear Boroa, Harp of Osorno, Pedro and then Neruda turns to his own relationship with the land, acknowledging his uselessness in the face of it.

XVI

Each in the most hidden sack kept

the lost jewels of memory,

intense love, secret nights and permanent kisses,

the fragment of public or private happiness.

A few, the wolves, collected thighs,

other men loved the dawn scratching

mountain ranges or ice floes, locomotives, numbers.

For me happiness was to share singing,

praising, cursing, crying with a thousand eyes.

I ask forgiveness for my bad ways:

my life had no use on earth.

Through the days, the months, the personages, the land, and the oceans, the glue that holds Still Another Day together is Neruda himself. At times the O’ Daly renders him, he sounds almost confessional, as in XVII when he writes:

I was that distant being

sickened by the carbon fumes

of the locomotive.

I didn’t exist, yet.

I had something to discover.

My poetry isolated me

and joined me to everyone.

That night I would

have declared Spring.

These sentences are very declarative, not the usual lilt one ascribes to Neruda. However, to my elemental Spanish (informed mostly by my knowledge of Portuguese), the translation appears to be right on. Is this unusually flat Neruda? I think so. One wonders if there isn’t an imperative as a translator to take liberties in order to bring the music back into the language. The strictest translator would stand aghast at such a suggestion. A translator like Bly would not be so ready to dismiss such a project. These are the two schools of translation as they have been passed down forever and ever.

Neruda reminisces about other items in his past, his grandfather Don José Angel Reyes, a kingdom the color of amaranth, how he once stopped in nothingness near Antofagasta. It is there Neruda seeks the purpose of a land (which parallels his own purposelessness in section XVI). He finds it in the sands of Isla Negra and at the whaling town of Quintay and eventually in the day itself and its rhythms, particularly those of the wave. It is that wave, the wave of humanity tied to a specific place, that does not die at the end — of course, it could be made uninhabitable due its being underwater as a result of global warming. I guess Neruda didn’t quite foresee that.

O’ Daly has made it his task for the last thirty years to translate the work of Neruda that was published after 1962. Still Another Day was the first book from this era of Neruda’s life that O’ Daly discovered back in 1975 in Modesto, and since then he has published five other volumes of Neruda’s work on Copper Canyon Press — Winter Garden, The Separate Rose, The Sea and the Bells, The Yellow Heart, and the Book of Questions. O’ Daly will have two more volumes out on Copper Canyon later this year. But with Still Another Day there is a range of styles and themes that will reward the impatient newcomer and satisfy those who have long been acquainted with his work.

What can be said of the poet who toils and lives with a single foreign poet through most of his/her life? This is dedication that cannot be easily dismissed. It speaks of an obsession that runs in the opposite direction of what most American poets, particularly young American poets are about — dedication to the self and one’s own work, especially the selling and promoting of it. O “Daly, like his poetic counterpart Neruda, has entered into the polis of poetry and we, as readers, are made richer for his efforts. Long may they continue.

Wednesday, April 9, 2008

KIM BARNES

Kim Barnes read from her Pulitzer Prize Finalist memoir entitled "Hungry for the World". She began her reading discussing the unwritten codes that we live by.

Kim Barnes reading from "Hungry for the World" [37:05]

Here she appears as 1920's silent film star Nell Shipman, famous for her role in the film "Back to God's Country" [1919].

Monday, April 7, 2008

FRENCH KISS DESTINY: THE DVD Live from the Heart of San Francisco. Written & Performed by MARVIN R. HIEMSTRA

Marvin Hiemstra is living proof that a poem can make a person smile, even laugh out loud, and still be filled with social relevance, high-wire poetics, and deeply-felt emotion. I’ve been fortunate to see Marvin’s live performances twice now; once in Oakland, and again in San Francisco. He brought down the house. Now his work can be enjoyed on DVD. (If this sounds like a blurb, it’s not. I just plain like this guy and his work).

Marvin created this DVD to, as he puts it, “suggest the wild and wooly kick of poetry before the Victorians so relentlessly glued poetry to the printed page and sat on it.” French Kiss Destiny is not Spoken Word. Nor is it Performance Poetry in the vein of Hedwig Gorski’s poem-songs. Marvin’s performances are more akin to a theatrical experience. He makes full use of his voice and body and even a magical ring that whispers phrases into his ear just when he needs them: “arrogant hangnail.”

There’s a playful tenderness at the heart of Marvin’s poems. He’s “never met a quark I didn’t like;” he tells us “angels never need to floss or wax or flush;” and he thanks Vaughn, a beloved cat, whose “twelve years gave us a gentle world.”

The production value of French Kiss Destiny is good, but no frills. Marvin is at center stage. The poems are clear and audible. The DVD is organized into three segments, shot at three locations: The Garden, The Heart, and The Sky.

The Garden is filmed in an urban garden with the sounds of the city in the background, including the occasional horn and siren. He introduces us to “Reincarnation for Beginners” and provides a remedy to an age-old problem of people falling asleep during poetry readings: a Chinese tone block that he raps between phrases. He also tells us, “Poetry is just like fishing. Some days you don’t catch a thing.”

The Heart is set in the silence of a Japanese mediation room—the sliding door slightly ajar to remind us there is still a world out there. “Some poets can’t find themselves,” he says. “Why don’t they look in the nearest mirror?” He asks us to “begin each day with a quick review of your destiny” and to appreciate coincidence, which “never let’s you down.” In one poem, Marvin tells a story of himself as an Iowa farm boy just having seen Marilyn Monroe in the movie “Bus Stop.” He pronounces Marilyn a Star to his traditional Dutch community, who simply chalk his enthusiasm up to hormones. As an adult, years later, after watching “The Prince and the Showgirl” on television, he reaffirms his youthful pronouncement. “Let’s just screw gender for a minute,” Marvin says. “Nobody will ever be that irresistible, with that much delicious class, ever again.”

In the final segment, The Sky, Marvin takes us up onto a rocky hilltop. “Where oh where is my audience?” he asks. “Ah, deep blue sky.” He invites us to make our own trek to the mountaintop. “Please take your poem to the top of the nearest cooperating mountain and shout it out. Listen to the echo.” He brings us back to sea level and down to the very ground itself, kneeling to bestow a kiss of gratitude. “I always want to kiss the earth.” Kiss. “After all, I owe the earth big time.” Kiss. “I wouldn’t be where I am without you.”

French Kiss Destiny: The DVD offers the viewer a refreshingly good time. What I hold closest to my heart is Marvin’s reminder of “the importance of human affection in this totally terrifying 21st Century.”

You can order French Kiss Destiny (Zippy Digital, 2007) directly from Marvin. His email is drollmarv@aol.com. The price is $14.95. Book Stores can order it from Books in Print: the Video Listing. French Kiss Destiny: The Book is forthcoming.

A final note: Marvin’s poems read well on the page, too. A Pulitzer nominee, Marvin often writes about the challenges of writing poems intended to be both read on the printed page and heard in performance. Check out his column, “Poetry In Spite of Itself,” in the Bay Area Poet’s Seasonal Review.

Marvin created this DVD to, as he puts it, “suggest the wild and wooly kick of poetry before the Victorians so relentlessly glued poetry to the printed page and sat on it.” French Kiss Destiny is not Spoken Word. Nor is it Performance Poetry in the vein of Hedwig Gorski’s poem-songs. Marvin’s performances are more akin to a theatrical experience. He makes full use of his voice and body and even a magical ring that whispers phrases into his ear just when he needs them: “arrogant hangnail.”

There’s a playful tenderness at the heart of Marvin’s poems. He’s “never met a quark I didn’t like;” he tells us “angels never need to floss or wax or flush;” and he thanks Vaughn, a beloved cat, whose “twelve years gave us a gentle world.”

The production value of French Kiss Destiny is good, but no frills. Marvin is at center stage. The poems are clear and audible. The DVD is organized into three segments, shot at three locations: The Garden, The Heart, and The Sky.

The Garden is filmed in an urban garden with the sounds of the city in the background, including the occasional horn and siren. He introduces us to “Reincarnation for Beginners” and provides a remedy to an age-old problem of people falling asleep during poetry readings: a Chinese tone block that he raps between phrases. He also tells us, “Poetry is just like fishing. Some days you don’t catch a thing.”

The Heart is set in the silence of a Japanese mediation room—the sliding door slightly ajar to remind us there is still a world out there. “Some poets can’t find themselves,” he says. “Why don’t they look in the nearest mirror?” He asks us to “begin each day with a quick review of your destiny” and to appreciate coincidence, which “never let’s you down.” In one poem, Marvin tells a story of himself as an Iowa farm boy just having seen Marilyn Monroe in the movie “Bus Stop.” He pronounces Marilyn a Star to his traditional Dutch community, who simply chalk his enthusiasm up to hormones. As an adult, years later, after watching “The Prince and the Showgirl” on television, he reaffirms his youthful pronouncement. “Let’s just screw gender for a minute,” Marvin says. “Nobody will ever be that irresistible, with that much delicious class, ever again.”

In the final segment, The Sky, Marvin takes us up onto a rocky hilltop. “Where oh where is my audience?” he asks. “Ah, deep blue sky.” He invites us to make our own trek to the mountaintop. “Please take your poem to the top of the nearest cooperating mountain and shout it out. Listen to the echo.” He brings us back to sea level and down to the very ground itself, kneeling to bestow a kiss of gratitude. “I always want to kiss the earth.” Kiss. “After all, I owe the earth big time.” Kiss. “I wouldn’t be where I am without you.”

French Kiss Destiny: The DVD offers the viewer a refreshingly good time. What I hold closest to my heart is Marvin’s reminder of “the importance of human affection in this totally terrifying 21st Century.”

You can order French Kiss Destiny (Zippy Digital, 2007) directly from Marvin. His email is drollmarv@aol.com. The price is $14.95. Book Stores can order it from Books in Print: the Video Listing. French Kiss Destiny: The Book is forthcoming.

A final note: Marvin’s poems read well on the page, too. A Pulitzer nominee, Marvin often writes about the challenges of writing poems intended to be both read on the printed page and heard in performance. Check out his column, “Poetry In Spite of Itself,” in the Bay Area Poet’s Seasonal Review.

Thursday, April 3, 2008

Congratulations!

Congratulations to The Great American Pinup team member Forrest Gander, who was recently named a 2008 Guggenheim Fellow in Poetry.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)