Friday, May 30, 2008

The Noulipian Analects

The essays in The Noulipian Analects that explore possible explanations for the dearth of women involved in Oulipo writing are particularly impressive. By looking at both the writings that are published and the dynamic maintained in classroom settings, works by Julianna Spahr, Stephanie Young, and the editors themselves prove provocative in their discussions of the ways constraint-based writing is frequently presented by male writers. An essay entitled “‘& and’ and ‘foulipo’” by Spahr and Young is a good example this trend. They write, for example:

We did feel this wok that uses constaint was ielevant, not to men no to women. We did not want to dismiss it. When we liked this wok by men we saw the eteat into constaint as an attempt by men to avoid pepetuating bourgeois piviledge, to make fun of the omantic nacississtic tadition, of all that tadition of fomalism. But at othe moments wi ween’t so sue that this was eally a feminist, antiacist self-investigation…It was often as if they wee using these techniques as a sot of dominance itual in the classroom, that at the women’s college whee we taught (although the gaduate pogram admitted both men and women) was aleady somewhat of a gende loaded space. (8)

While using constraints themselves, Spahr and Young present a complex vision of experimental writing that suggests the oulipo tradition remains at once subversive and patriarchal. Raising significant questions about the ways gender politics encourage and/or stifle art, “‘& and’ and ‘foulipo’” offers goals for the Oulipo community to strive for in the twenty-first century. Like many of the literary essays in The Noulipian Analects, this piece by Spahr and Young assesses and critiques while acknowledging the possibilities for activism via the tradition of constraint-based writing.

Other essays in the anthology treat such diverse themes as electronic writing, “‘Axioms’ of Oulipian,” the option of revealing or not revealing constraint to the reader, and new media writing. Although the book presents a wide range of ideas pertaining to constraint-based writing, the theme of new directions for Oulipo writing continues to resurface, raising questions about the types of writing that belong or don’t belong in the canon. I enjoyed Brian Kim Stefans’ essay, “Electronic Writing (or Privileging Language),” which discusses both the shortcomings and the opportunities offered by this medium, evaluating whether or not it really should be classified as poetry. He writes:

I’d also like to argue that in much electronic writing…language is being used to solve a formal problem in the artistic project—often to make the experience more concrete or to found out a metaphor—and the electronic elements of the project have not come around in order to solve a problem in the literary effort. Which is to say: digital art quite often needs poetry more than poetry needs digital art, though one would think in the field of electronic writing the latter should be more true. (61)

By implying that in poetry, language should take priority over the visual, Brian Kim Stefans presents a vision of experimental writing as being grounded in the techniques of traditional poetry. While acknowledging the potential for avante-garde literature to subvert such conventions, he also suggests that there’s a limit to what aspects of more traditional poetry can be abandoned altogether. Just as other essays in the collection delineate new possibilities for Oulipo writing and other experimental endeavors, Stefans’ essay and others strike a cautionary note in pursuing them.

All points considered, the Noulipian Analects is a diverse and provocative read, ideal for experimental writers and scholars alike. Five stars.

Tuesday, May 20, 2008

THYLIAS MOSS—TOKYO BUTTER

I remember a graduate seminar at the University of Minnesota for Professor Bruce Lincoln’s discourse analysis class. Lincoln was a tough-minded, straight talkin’ son of a gun, and he would quickly disabuse you of any notion you might have that was even the slightest bit fluffy. But he was willing to take on all comers despite their area of expertise. For the final project of the class we assembled at this home and listened to various students give a talk or presentation. One woman from the theater department began her project that I believe had something loosely to do with the notion of the construction of identity. She sat down with an array of greasepaints and a mirror. She proceeded to apply one layer of paint to another, going through the changes of several different hues, until her face was very dark. Then she continued to reverse the darkening by lightening her face with many more applied layers of paint, each time dabbing on a little bit more until the hue of her face had lightened considerably. This process continued for some 30 or 40 minutes while the rest of us patiently watched her apply make-up to herself. Certainly we had gotten the gist of it after 5, but it was interminable. We all agreed that what she was doing may have been art, but we weren’t sure whether it was something we could ever tolerate watching again.

So it is with Thylias Moss in Tokyo Butter. The amount of infinitesimal detail from the lived life of the speaker (presumably Moss herself) and Deidre (or is it Deirdre), a dead cousin, offered up in the space of the book is mind-numbing. I haven’t experienced such a blankness of mind since I read Geraldine Kim’s Povel, another book that nodded toward the great concept but whose execution of it left me baffled. Tokyo Butter is no Povel, thankfully. Moss is much more generous, and occasionally, when she departs from chronicling every last angstrom traversed in her life, she provides some interesting forays into other materials, not the least of which is the work of Utamaro and the method by which Paul Tessier devised his surgical techniques on the skull.

These bits are swirled together with so much other ephemera that they are lost in the shuffle. When Moss does focus on them, it is for just a brief moment and then they are gone. Sometimes they reappear later in another context. Often they do not. All of the info-bits dumped into her long lines serve to illustrate the concept and theory behind her work, something she calls Limited Fork Poetics. From the back of the book (though you can read the entire thesis [“A Generalized Mapping of Limited Fork Poetics as of May 2006”]) she writes:

Limited Fork Poetics (LFP) believes that Poetry is a complex adaptive system, and because of that, page is unrestricted, and means “location of the poem.” Some poems will inhabit places for which there is not yet means of detection or interpretation. A dynamic poem is event, occurs in time, and in its totality includes all versions, all thought that the person encountering a form of the poem supplies—this can be a reader (who remakes the poem through interacting with it)or what is considered the primary maker (poet) of the poem. A dynamic poem is a system of poetry, so (shifting) interactions between the subsystems (all that the poem contains) is essential to making (mutable) meanings. A dynamic poem hosts interacting language systems(including sonic, aural, and visual forms besides/in addition to/instead of text). The activity of interacting systems takes place on all scales immediately. The landscape of a single poem can include multiple areas of constituents of the poem taking shape in multiple forms (including sonic, aural, and visual forms besides/ in addition to/ instead of text) simultaneously, in varying degrees of stability (forms of accessibility/incoherence). There is no definitive beginning or ending. A portion (or portions) of a poem is joined, is left in progress. Interactions at a given time help determine the observable stability or instability (and the perceived direction[s] of the activity). Metaphor is a tool of navigation that can enable instantaneous access to other event locations on any scale—akin to navigating wormholes. The journeys to and from what is considered the same metaphorical events may not be identical.

Amid the extensive pomo jargon and barrage of theoretical language, I derive the notion that Moss’s poems are supposed to be complex adaptive systems, which are inherently limitless and open to multitudes of artistic maneuvers (“the page is unrestricted”) and multitudes of interpretations. In short, the poem is the be-all and end-all of anything the poet or reader desires. However, my great concern is that in inscribing this space for free association and scripting, if it is determining anything at all. Certainly as I read large portions of Tokyo Butter and feel my mind go numb from the excess, I sense there is nothing to be determined. Perhaps this quavering vagueness is the feeling I am supposed to be having, but if it is, I wonder why this is the desired outcome for a reader.

Now I know that Moss is only invoking the term complex adaptive system in a very metaphorical manner and does not wish to be taken literally that her project is trying to create the equivalent of a complex adaptive system in poetry, but I wonder why this scientific terminology is invoked unless there is going to be some attempt to come to terms with and understand the real discipline that surrounds systems theory. Is this attachment to scientific language just an affectation?

For instance, it would have been useful to address some of the interesting qualities of complex systems such as what is noted in Duncan Watts’s excellent book for the lay reader Six Degrees: The Science of a Connected Age which discusses systems theory and complex adaptive systems with respect to economics and sociology. Towards the end of the book Watts provides this overview of some of his insights about networks:

claiming that everything is a small-world network or a scale-free network not only oversimplifies the truth but does so in a way that can mislead one to think that the same set of characteristics is relevant to every problem. If we want to understand the connected age in any more than a superficial manner, we need to recognize that different classes of networked systems require us to explore different sets of network properties. In some cases it may be sufficient to know simply that a network contains a short path connecting any pair of individuals, or that some individuals are many times connected better than others. But in other cases, what may matter is whether or not the short paths can be found by the individuals themselves. Perhaps it may be important that in addition to being connected by short paths, individuals are also embedded in locally reinforcing clusters, or that they are into so embedded. Sometimes the existence of individual identity may be critical to understanding a network’s properties, and at other times it may not be. Being highly connected may be of great use in some circumstances and of little consequence in others—it may even be counterproductive, leading to failures or exacerbating failures that occur naturally. Just like the taxonomy of life, a useful taxonomy of networks will enable one to unify many different systems and distinguish between them.

I fear that, as a system, what Moss has constructed in Tokyo Butter is neither complex nor adaptive. The result is more like a random graph, a system of nodes randomly connected together without respect for distance and likelihood of connectivity, rather than as small clustered groups tied together by a few overarching connections which is most often the characteristic of a complex adaptive system.

I could go on and question whether the “Limited Fork” has anything to do with bifurcation theory, but I know I would be taking what Moss offers in her theoretical speech way too literally. Though I must admit that bifurcation theory could be readily associated with the phase transition of a complex adaptive system. However, with Moss her Limited Fork poetics is, if anything, hardly very limited at all.

Moss does not make apologies for not recognizing boundaries. She sees her work as not recognizing any limitations because in putting up a limit in one’s work, one is privileging certain material that is included in the poem over other material that does not get in. Her project is a radical flattening of all material so that the most quotidian and droll information is not positioned any differently than “poetic language” that is immediately recognizable as such. It is a project of radical inclusion. It does this in order to avoid excluding anything. However, one person’s exclusion is another person’s selection. We all have preferences, and it is impossible to say that any work doesn’t have “symptoms.” isn’t symptomatic of certain things that draw our attention as opposed to others that don’t. I would go as far to say that all informational scanning has an aspect of selection associated with it. I do not randomly search for info when I jump on the net. It would take too long for me to come across something that might resonate with me, and I don’t have that much time on the earth to sift through all the info. Poetry, it seems to me, relies on some kind of selective attention for the reader to engage and trust the voice. Otherwise, one might get the same experience from a poem as one does by randomly clicking on hyperlinks, the flarfist’s game. I suspect that this kind of experience is not what poetry readers are looking for. But perhaps it is the experience of the radically distracted, those in perpetual need of being thrilled. Maybe this is who Moss is writing for, and she suffers only from a bit of a marketing problem by appealing to the more dull-witted poetry reader.

I might also offer the observation that Moss, like Geraldine Kim of Povel is not part of the WASP mainstream that is the dominant culture in the US, a dominant culture that puts up many roadblocks (read as “limitations”) to those who are not viewed as part of that mainstream. Both writers want to include everything in their work with particular emphasis on the minutiae of everyday life.. Is this a symptom of having so many limitations placed upon them that they may want to so radically unshackle themselves?

Without any limitations at all about what is included, readers must come to terms with the fact that any rendering of a life and its informational byproducts is on the same plain as any other. Anything that is collected is equal to anything else, perhaps even equal, by implication, to that which is not collected.

The effect is almost like one who is drunk on information, falling in love with it for the first time. So there is a great rush to include everything that is found like a beginning composition student just beginning to flush with excitement after discovering ProQuest or the Project Muse scholarly databases. What is even more pernicious is the fact that Moss dresses this up in a conceptual framework that justifies the practice. All is done in the name of a complex adaptive system that can adapt to any information thrown into it and, churned, (like butter, to use a much maligned metaphor of Moss’s in the book) will be integrated and functional. I felt like I was reading flarf at the paragraph level. Unlike flarf where short words and phrases were juxtaposed with other short words and phrases to produce an amusing word salad (wasn’t the point of flarf always irony?), Moss incorporates much larger blocks of information. Often this occurs without much metaphorical or thematic value being added. It is simple information dump offered in the name of poetry and expression. All of it goes to reaffirm what has become my growing suspicion: what goes on in the privacy of a person’s home is between her and her search engine.

But apart from this theoretical quibbling (though it is interesting to note how Moss, reminiscent of the best of the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E movement, has dressed up her poems in a poetics that is potentially more enticing than her poetic output), I should try to say something about the poems themselves.

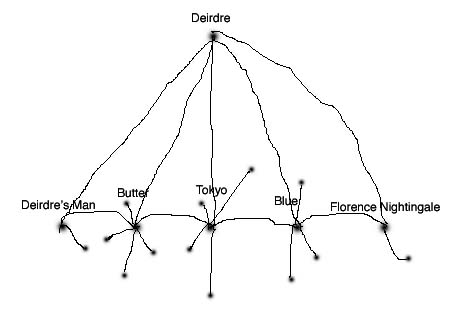

The central poem in the collection is “Deidre: A Search Engine.” This piece is an assemblage put together with the help of Google, something that Moss seems to refer to as a Google odyssey [so much for complex adaptive system; the main metaphor for this piece is “the trip”]. The “system” (assemblage) that Moss puts together is of a string of info-bits connected at the terminal ends to each other with the theme of the missing cousin Deirdre folded into the loose structure for the purpose of some semblance of coherence, a kind of hierarchical node that many parts of the system immediately relate back to.

One important aspect of the poem that makes it seem more like trip than system is the glaring absence of any kind of prolonged connection (except that of the Deirdre variety) between elements (read nodes) at the beginning part of the poem to those at the end. Apparently, all connections that tie in the superstructure of the poem must run through Dierdre. This, as I have mentioned before, is not a quality of a complex adaptive system. Complex adaptive systems generally employ more connection between sub-nodes. They do not all connect back to the primary node. Such a system architecture is inefficient. The basic architecture for this piece is of the thread with a few connectors to the main theme (main node) of the missing Deirdre.

Another manner in which the poems and book fail to serve as complex adaptive systems through their structure is if we consider the notion of node failure. Often within systems, if a particular node fails, then a cascade effect will occur which will eventually make the system shut down. An example of this might be with the electrical grid. If an important node goes down within the electrical grid, the excess capacity is pushed onto another part of the network and thus makes it more susceptible to failure. And if this second connection in the grid goes down, then even that much more capacity will have to be transferred.

Let us look at how the poem “Diedre: A Search Engine” is structured. [Pardon my crude Photoshopping.]

If one agrees that this is how the poem is structured, with the main node of “Deirdre” being the point of connection for all of the subsystems of the poem, then what would happen if that main node would be knocked out? I would argue that system failure would be inevitable. There is no considerable linking between the lower orders of the system.

I will quote from John H. Miller and Scott Page’s book on Princeton University Press Complex Adaptive Systems: An Introduction to Computational Models of Social Life

The behavior of many complex systems emerges from the activities of lower-level components.

Ostensibly, What Moss has created is a linear system with one hierarchical node.

This poem and Tokyo Butter as a whole lacks this kind of linking between subsystems (with the possible exception of the many references to flowers sprinkled within the poems . . . however these are usually just brief mentions and do not serve as any kind of prolonged attraction within the system of the poem). I can certainly imagine what a poem that might have more subsystem connections would look like, but with that kind of poem it would be difficult to talk of what it is about though I think most readers would be able to discern that a number of attractors were resonating with each other in interesting ways (and not in random ways).

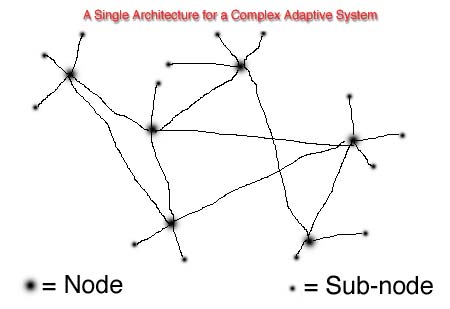

On the other hand with a complex adaptive system:

Each of the subnodes has a considerable number of connections to other subnodes, which are, in turn, minimally connected to other sub-sub-nodes.

But, by indulging in a little bit of mathematics, we can begin to speak of how these systems operate.

According to Stuart Kauffman in The Origins of Order there are two important variables to consider:

N=the number of nodes within the system

K=the average number of inputs to each node in the system

When K=N (a situation where every node in the system is connected to every other node) this is a completely random system (in other words, a random graph). These systems are highly chaotic.

However, as the value for K approaches 2, the system undergoes a phase transition from being a disordered regime to being an ordered regime; in other words, order begins to crystallize. These systems are poised nearr the chaotic regime and are ones which possess the most ability to adapt (self-organize) yet are still fairly robust and stable. They are ones which closely resemble those of natural biological systems. They abide at the edge of chaos.

The system I have drawn above utilizes 20 nodes; therefore, N=20

There are 44 inputs to these 20 nodes; therefore, K=2.2. This system is slightly into the chaotic regime, but it is approaching the K=2 range that Kauffman mentions.

Also, quite puzzling to me is the manner of the connection in this assemblage. Many of the connections forged are quite random (Florence Nightingale—Florence, Alabama), (blue nightingale, blue tongue, blue mouth, blue tattoo, methylene blue, etc), (“Snow often articulates as feathery as implications of her name,” “the living snow,” “The best historic attempts to photograph snowflakes . . .”). It is almost as though one could have focused on any other noun or verb in the text and built up connections to other texts based on those nouns or verbs. For that matter, Moss might have focused on adverbs or articles. Though perhaps I am dense, I don’t very readily see how the various connections relate to each other with any semantic force. The connections between the items in the poems are done with no apparent interest in making anything other than surface connections. The main aesthetic value that Moss is going after in this approach seems to be raggedness (as one can glean from the aforementioned “A Generalized Mapping of Limited Fork Poetics as of May 2006.”

The structures formed by complex adaptive systems, even when they occur within bounded or regular spaces, tend toward manifestation (especially over time) of irregularities and unpredictable details (a kind of raggedness) possible

within the limits of the boundaries (that are [or become, for some interval of

time] generally fixed though not infallible or immutable or without signs of

wear, signs of consequences of existing) of dynamic events. Clouds, and trees

with their bifurcating root and branch systems at either end of a comparatively

linear trunk, are both examples of complex adaptive systems and products of

complex adaptive systems. Clouds tend to form within the boundaries of clouds

though the precise details of each cloud formation as it appears at various times

from various angles are not predictable. The same is true of the human body and

of most natural objects and natural systems.

This aesthetic of raggedness (in bold above) is prevalent and may go a ways to explain Moss’s lack of restraint. Some of the moves she makes can be seen as either endearingly idiosyncratic or outright embarrassing. Here is a section from “Deidre: A Search Engine” on page 95 right after one of her riffs on butter, where she ends that section with “These are cures in alternative medicine. / This is the way it should go. Butter residencies / in apothecaries”:

In under an hour, a man with one leg,

the best way to single him out of the crowd doing this,

carved an entire butter army

and then there was a contest to defeat it, and it was defeated,

and an entire army was in one stomach. The carver had carved

no weapons for his army. Every soldier

was a general soldier, nondescript

—necessary for the time constraint, the detail an hour could hold.

They had no mouths.

Where he pushed in with fingernails, resulted at best in chins.

They had no mouths.

In the end, he went home successful

until daybreak

when the yellow flooded

so thoroughly even his spirit

was back in the butter

so he took a bath.

I am at a loss to accurately decipher the tone of this offering. I am not sure if some of these lines are meant to be funny or not, like “he was back in the butter / so he took a bath.”Or is this just a documentation of the minutiae of a life? Is the whole butter army supposed to be taken at face value or is this a brief humorous jaunt? I’m sure the reader-response theorist will jump up and say—make of it what you want. [Note: I don’t think the reader-response theorist really wants me to do that for fear I might deface the page, write over lines, cross out large sections.] Similarly, on page 94 Moss writes “The vow of poverty taken on by yeast, / single cells in the budding Order Saccaromyces. / Yeast priests.” I’m pretty sure that this is supposed to be humorous rather than just a flight of fancy, and I hope that I am the only one who has to pause a moment to decipher the tone of that statement. But there are many other instances where Moss’s wordplay makes me uneasy about whether I should snicker or marvel at her linguistic play, her verbal agility. I am often caught in these similar moments when I read Heather McHugh. McHugh is a great biofeedback poet. I read her when I need to tell if I’m having a good time or not.

I am also curious why the spelling in the title “Diedre” does not correspond to the rest of the book where the spelling is “Deirdre.” Only one reference in the poem seems to speak to this:

[at various times, goat has translated as ghost, ghost as goat

and continued after the error was exposed

for the sake of poetry,

for the beauty of leaks,

for the conquest possible only through translation]:

The main justification seems to be that this kind of variance can be exercised in the name of poetry. I guess I am supposed to be left wondering, and for that, I will be a better person for letting this question linger. Or perhaps the proofreader’s eyes glazed over.

I have looked at Moss’s earlier work from Slave Moth and The Last Chance for the Tarzan Holler, and in it she appears to show more restraint than she has in Tokyo Butter. I am able to derive more sustenance from those efforts. Perhaps I should stop trying to eat poems and just be inside them.

There is a good deal of exciting research that comes up from a variety of sources. During the course of reading Tokyo Butter I have learned terms like williwaw and druse, vitiligo and arowanas. These multi-syllabic gems are impressive. I have used williwaw to impress the mail carrier and the neighbor’s exterminator already. At this molecular, if not sub-atomic level, Moss delivers. But just as often Moss will torture many of the words/subjects she uses by making them undergo fantastical transformations. A good example of this is in “The Culture of Snowmen” where the snowmen seem, like the majority of Moss’s oeuvre, to have no limits. This is the delimited snowman, atomized, then put back together. With all of this fantastical morphing, the metaphor of the snowman (to stand in for human men?) becomes unstable. Again, the raggedness.

There are times when her selection seems right on, like in this passage in “The Magnificent Culture of Myopia”

our whole house of sons, drums,

saxophones, keyboards, replicas of hippos, and canaries

are now beneficiaries of peaches, heirs of fuzz,

scant fur of beginner mold about to bless

bread with blue beards

Other times, I find myself wading through my exasperation at the verbal flourishes:

and my presence which must be dealt with gets churned into

the meaning of what occurs there.

Assumptions butter the mind or coat it so that

what it doesn’t want can’t easily get through: butter barrier

greased pig thinking but once on your skin

butter can feel like your own secretion, your own rich oil:

bounty ooze crown melt —if only there was toast

in the picture, deli buns, biscuits, croissants, beignets

more obvious reasons to lay it on thickly, but sticks of butter

come architect-ready to build a house, plantation columns

and nothing is easier to sculpt

than pale butter skin all the way through, bone-free, dull knives

glide renewed, resuscitated: ghee glee.

Come to think of it, the exasperation occurs at a ratio nearly 5 to 1 with respect to those times I am imagistically or sonically satisfied. What is wrong with me? Let’s see. Butter is churned. It butters the mind and puts a protective barrier over it so that nothing can penetrate. This is similar to the secretion of the sebaceous gland. Then toast is introduced (and other delicious bakery items). Then the butter is used as building blocks, which quickly transforms us back to the notion of butter as skin.

All of this one in one stanza. One stanza in a poem that lingers for four pages, offering us more of the same along the way. God help us if Moss ever develops a penchant for rhyme as she does for metaphor. The result would put Dr. Seuss to shame.

Also with her venture into Limited Fork Poetics, Moss has begun to put together multimedia presentations of her work. This page at Limited Fork provides a collection of this work. One of the pieces that is posted thereThe Culture of Funnel Cake [mp3] is taken from Tokyo Butter. Moss’s son, Ansted, provides the background keyboard and Moss proceeds to half-sing/half-chant every line. The recording does not extend to reflect the entire 9 page poem. This self-described elliptical offering seems to meander in phase space between the abscissa of women who wait too long to realize their fertility and the ordinate of the dominant state of living things.

While Moss provides an interesting direction with her POAMs [products of the act of making—read as “improvised ad hoc pieces”] that fuse spoken/chanted word, manipulated images and ethereal keyboard soundtrack, I find that these “systems” also tend to make my mind drift for their bricolage approach to making videos. However, because she is one of the few poets out there willing to venture into the videopoem world in academia, she should be entitled to carve out her trace in a world where conventions are minimal. She seems to embrace the “go for it” spirit with these efforts. Sometimes, though, like with her poems, the presentations seem overly long. For example, I challenge anyone to listen to [The Song of Iota] with anything like full attentiveness.

With so much of the videopoem seeming like it owes a credit to the 30-second spot, I can’t help wondering if there aren’t lessons to be learned from the advertising industry for videopoem makers. Moss decidedly undermines all of that by diffusing the attention of the watcher. Her videopoems seem to be the antithesis of locating power squarely at the center of the presentation. [Yet it is curious how many of Moss’s videopoems feature images of herself.] She seems unconcerned if we get the tag line. She uses the language of “interacting language systems” to describe the multi-layered vocalizations. Another word for this might be cacophony. The effect of simultaneity is achieved. Again, though, I question the “interaction” of the utterances. Often there seems to be a talking-at-cross-purposes that is going on. I suppose this brings us back to Moss’s prevailing aesthetic of raggedness.

The raggedness defines the POAM, and it defies the description of poem as a consumable. I guess I can’t help wanting the poem as it is performed to be something that is ultimately reflective of experience, something where a person can say “this is what happened”rather than the poem as happening itself. I never understood rave culture either. But strangely enough, I have found the work of the Situationists to be interesting grist for the mill . . . perhaps because the cultural critique was sharpened in their presentations. Too often I get the feeling that Moss’s POAMs are advertisements for herself or the technology she uses. Or both.

Perhaps I am stubbornly boneheaded in my thinking that a poem is a “speech act,” one which reflects a community of speech acts and tries to place itself within that community by connecting to the history of those speech acts. I’m sure that puts me firmly within the grasp of tradition in the eyes of someone like Moss, but I don’t really feel like a traditionalist.

It is interesting to me that the types of inflection Moss uses in her videopoems are that of a somewhat melodic chant and a voice-in-slow-motion when she wants to underscore words for their weight. There is no throwing of one’s voice or snarkiness or any other kind of affect in her voice. In this manner, the renditions of her poems seem disconnected with the community of speech acts that I mentioned above. I suspect, though, that these observations of mine would be met with a rejoinder that poems are not “acted, “ but spoken. I would like to welcome anyone who makes such a rejoinder to go see a poetry slam. There is where poetry meets drama. The spectacle is upon one there, but I, usually, am not there. However, I am advocating for a larger vocabulary of vocal presentation than melodic chant/song and straight spoken “reading” voice.

As I look back onto what I have written about Tokyo Butter, I realize that I have been fairly harsh in my comments and criticisms. I wish also to applaud Moss’s individual spirit that makes her go it her own way. She deserves credit for acting on her vision for the possibilities of what a poem could be or should be. She trusts her own imagination in ways that few dare to emulate. Certainly I am not as daring. I don’t want to seem as if I don’t get her brave new world. But perhaps I don’t. Perhaps my resistance to her work is also because I have spent so much time thinking about how the ideas of those who are pioneering the new science of networks relate to contemporary poetry. I think it is important that if one invokes those ideas, even in the process of making them one’s own, one is responsible for upholding the integrity of those ideas and really coming to understand them, not just appropriating them for the sake of artistic expression. For me, poetic license doesn’t extend that far.

Like everything else, treading on another’s territory, in this case the intellectual territory of network science, is more bearable if it is done with some appreciation for what is there and what has been established. If not, then such appropriation looks more like a wildly exploitative move. Or worse yet, a dalliance. A whim that that fails to take the efforts of others into consideration.

POSTSCRIPT: "The Unbuttered Subculture of Cindy Birdsong" from Tokyo Butter. One of my favorite pieces in the book though I'm still not sure about the tone of "unspecified backup bird" and "shrunken heads don't need a redundant trip to the gallows" and "atomic and subatomic groupies." Perhaps I've just had a bad week and my sense of humor has been compromised. I love that radation-altered sunflower with the open head though.

Interview with Thylias Moss at Lily. "a study of the limits of precision at the limits of precision"?

"Dan, I lack a proper mindset. That is why precision is my goal. I have a mindset of awareness of simultaneous active zones of interactions visible differently through each lens used." I'm not sure what this means, how "precision" and "diferently visualized active zones"are related but I think it helps me contextualize a good bit of her output in Tokyo Butter

Tuesday, May 13, 2008

Skirt Full of Black by Sun Yung Shin

Skirt Full of Black. Sun Yung Shin. Coffee House Press.

What happens in a world where language fails us? Sun Yung Shin’s poetry collection, Skirt Full of Black, fills in the gaps between language and between the past and present by crafting poems that dip from many pots. Shin’s eye is a critical one: This poet is definitely conscious of the social ramifications of not only her poems but also of different cultures’ practices, the news, traditions, and faerie tales. The poems in this collection are like a collage: there are different voices, material, and subject matter. What unites the pieces of these poems is their critical gaze: nothing escape’s this poet’s eye. The world seems open for the taking and for examination.

From the beginning, Shin’s intentions are loud and clear: the first poem, “Macro-Altaic,” takes on assimilation and “the color of death, Western clothing.” This poem maps the collection’s journey, and its attempts to make sense of what is lost between languages and what is lost at the cost of assimilation. In this first poem, Shin writes: “Date on the red book from Korea, year prior to birth, folk tales, year of gestation, folk tales, year a maternal body with double interior.” Time is marked in Korea’s color – red – and the past is referenced, as is the feminine and its misrepresentation. Shin’s work in this collection is focused around the “double interior” of language: Through a collage of perspective, the poems address what is missing, neglected, and/or oppressed.

And yet, with all the differences between English and Korean, there are still boundaries. In the collection’s first poem, Shin addresses this: “…not easy to draw boundaries in any language between what is a word and what is not a word and Korean is no exception.” What is and what is not are two dichotomies that exist in each language. This idea aligns to what is implied about each culture’s treatment of women: they are told what they can and can not be. She writes in “Flower I, Stamen and Pollen”:

Even the knot of her shadow reckoned him starlet, sparrow, hummingbird.

Her youngest older brother. His devotion was positively medieval.

Sanctified. Gilt. He had made a deaf rope of roots and her mute mouth

stained abundant with the prophecy of berries. A replica of paradise. Their

mother’s womb he scraped clean. Red-empty-red. Her favorite lineage.

Women are protected only to be used as a vessel, for their womb. The poem is as gruesome in its imagery as Grimm faerie tales. However, instead of the old faerie tales that were used to warn women against leaving or disobeying their parents or husbands, this faerie tale is a feminist response to a life of oppression, a life of control.

The major accomplishment of this poetry collection is the collection’s fifth section, “Vestibulary.” Here, Shin takes the Korean language (hangul and the old Romanization) and creates poems inspired by the traditional meanings, sounds, and associations of this language. Language is notoriously biased, notoriously linked to the patriarchy (historically made for men by men), but Shin takes this language on and gives each character, a story, a new life.

Women and their ethnicity are recurring subject matters: Shin gives women their voices and throws a spotlight on the generalizations of ethnic groups. Sometimes these spotlights seem to drown out their subjects. Like someone screaming from a rooftop, the reader can sometimes nod their head with frustration and mouth, “I get it; I get it.” Shin is at her best when she attacks subjects in a creative fashion and through metaphor.

It is in this section that Shin that her politics and poetics learn how to work off of one another make sweet music together. It is here where the collection’s ideas come together and coalesce. “Vestibulary” is a true accomplishment: part dictionary, part critique, part association, and a blending of perspective and culture, this piece of the collection is strong because it touches on many things at once. Here, Korean culture can meet Western culture. Here, what can not be explained by one language can be explained through their combination.

The pieces of “Vestibulary” touch not only on the literally meaning of the Korean language but also its look. Many of the poems take on the shape or allude to the shape of the Korean characters. For example, “kiyek,” is a poem based on a Korean character that looks very much like an upside-down “L” (and looks something like this: ┐). Here, Shin writes:

stained raw your lover’s knee,

precipice;

scythe, raw grain;

late, wet harvest;

half-chair in silhouette.

The poem’s language alludes not only to Korean culture and the tug-of-war relationship between English and Korean (i.e. “the half-chair in silhouette”), but the poem’s spacing and line-length links strongly to the character’s look: its shape and the thickness of its line.

Forever in limbo, Shin makes sense of the world through purposeful collision. English and Korean come together without losing their individuality. That’s not to say that this collection doesn’t explore the multitude of issues involved when two cultures not only compete for standing but oppress its members. The poems in this piece are loud with their discussion of

What one language can express, another can not, and Shin asks for more language, another language to speak for things that are unspeakable. In “Half the Business,” she writes:

We should all have two languages, one of our childhood, and one of our

deathbed.

God, let those two be the same.

No more songs about bureaucrats, armies, a confetti of human hair.

Shin asks for a language that can shrug off the confines of the patriarchy, a history of misogyny. Additionally, Shin seems tired of what has been said again and again in the same languages. The poem continues with “Every woman a scholar dissecting her own body, eating her own words / until the end of words.” Here, language again is linked to the oppression of women. To study language, to be scholar, one must “eat her own words,” one must see the limits of language. This love-hate relationship is one that is key to the poems in this collection, key to Shin’s plight. A poet may love language, but as a woman, language is as oppressive as anything else in the world. As someone balancing two languages – Korean and English – the struggle is even more complex.

Shin’s poetry collection is a revolving door of perspective. Like a skilled juggler, Shin flips the coins again and again to peer in on the reflections, the differences and the similarities. What is a poet to do when language fails her gender, her ethnicity? This poet takes the languages that have failed in the past and combines them. The resulting collage of perspective and language tackles its subject matter head on. Though the subject matter of these poems is loud and ablaze with a critical eye, the poems do not lack in sound play or form. Shin marries her poetics and politics, and the resulting poems will challenge a reader’s ear and assumptions. Language may have its limitations or its issues, but it is capable of redemption.